Fur Farming Brief

Fur Farming: what it is, how it works, and why it matters

Fur farming is the intensive production of animal skins (“pelts”) for fashion. It typically involves keeping thousands of animals in rows of wire cages, breeding them for coat colour and pelt size, and killing them when their fur is judged to be at its “prime”.

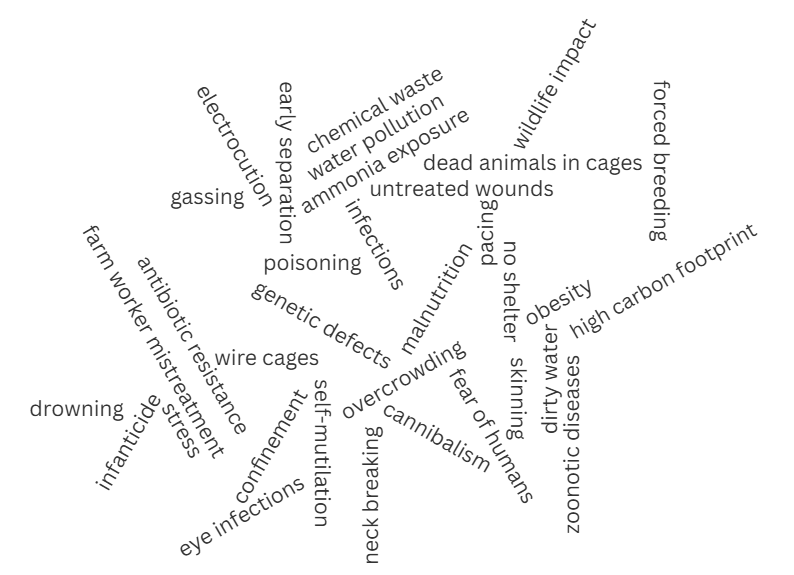

This page summarises what reputable scientific and economic evidence shows about fur farming today: the conditions animals are kept in, the methods used to kill them, the wider risks (including disease and environmental impacts), and why “welfare standards” and certification schemes do not resolve the core problems.

Jump to:

Which animals are farmed for fur?

How animals are kept on fur farms

What the science says about welfare on fur farms

Killing methods used for fur

Fur farms and disease risk (biosecurity)

Environmental impacts

Certification, “standards”, and traceability schemes

Is the fur industry growing or declining?

Explore the data

Sources

Animals such as foxes are kept in small wire cages on fur farms, regularly suffering serious welfare problems as a result. This conditions are true on all fur farms, whether in Europe, North America or China (Finland, 2023)

Which animals are farmed for fur?

The main species farmed for fur include:

American mink

Foxes (including red and Arctic foxes, sometimes called “silver” and “blue” fox)

Raccoon dogs

Chinchillas

In Europe, these are the key species assessed in the latest major EU-level scientific opinion on fur-farmed animal welfare: EFSA (2025) Welfare of mink, foxes, raccoon dog and chinchilla kept for fur production

How animals are kept on fur farms

Fur farming systems are usually designed around efficiency and pelt yield, not around the biological needs of the animals being kept.

Across common production systems:

Animals are typically confined in small wire-mesh cages, often in long rows under simple roofing (sometimes open-sided).

The cage environments are generally barren, with limited opportunities for natural behaviours such as roaming, exploring, digging, swimming (for mink), hiding, or meaningful social contact.

Confinement and lack of stimulation are linked to stress, injury, and abnormal behaviours.

For a detailed scientific overview of how these systems affect mink and fox welfare, see: Pickett & Harris (2023) The Case Against Fur Factory Farming in Europe.

What the science says about welfare on fur farms

In 2025, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) was asked a straightforward question: whether the most important welfare harms seen in fur farming can be prevented or substantially mitigated within the current cage-based systems.

EFSA’s conclusion is stark. In its abstract, EFSA states that: “In the majority of cases… neither prevention nor substantial mitigation… is possible in the current system.” (EFSA, 2025)

Across all assessed species, EFSA identifies common top welfare consequences including:

Restriction of movement

Inability to perform exploratory or foraging behaviour

Sensorial under- and overstimulation

(EFSA, 2025)

EFSA also identifies important species-specific harms (for example, handling stress in mink and foxes; locomotory disorders in Arctic fox; isolation stress in raccoon dogs; and predation stress and resting problems in chinchillas). The common thread is that these harms are driven by cage size, cage design, and barrenness — i.e., features that are fundamental to how fur farming is currently carried out.

For a deeper scientific critique of why cage-based systems and associated “welfare schemes” do not solve these problems, see: Pickett & Harris (2023) The Case Against Fur Factory Farming in Europe.

Killing methods used for fur

Fur farming involves killing animals primarily to preserve pelt quality. Across producing countries, commonly reported killing methods include gas, electrocution, and other techniques designed for speed and throughput.

A detailed welfare review covering housing, handling, and killing practices in European production systems is available here: Pickett & Harris (2023) The Case Against Fur Factory Farming in Europe.

(If you’d like, this section can be written in a more “plain language” style or a more technical style, depending on your audience.)

Fur farms and disease risk (biosecurity)

Fur farms can create avoidable public health risk because they:

confine highly susceptible species in large numbers,

involve frequent human contact, and

can enable rapid pathogen spread under intensive conditions.

International agencies have specifically assessed risks connected to fur farming in the context of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). See the joint risk assessment: WHO/FAO/WOAH (2021) SARS-CoV-2 in animals used for fur farming (GLEWS+).

For a fuller Facts About Fur explainer focused on this topic, see: Fur & Biosecurity (Facts About Fur).

Environmental impacts

Fur production has a significant environmental footprint, including impacts associated with:

feed production for carnivorous species,

waste and emissions from intensive farming and manure management,

and pollution linked to the broader supply chain.

For a science-led review focused on fur’s environmental impacts, see:

Respect for Animals (2021) The Environmental Cost of Fur (full report)

Respect for Animals (2021) The Environmental Cost of Fur (executive summary)

You can also explore our dedicated page here: Environmental Impacts of Fur (Facts About Fur)

Certification, “standards”, and traceability schemes

The fur industry often points to certification and traceability schemes (such as on-farm welfare scoring or product labelling) as evidence of “responsible” fur.

However, a recurring problem with welfare certification in fur farming is that it is typically designed around the limits of the existing cage system. That means it can end up benchmarking farms against “best current practice” within a fundamentally restrictive system, rather than delivering conditions that meet animals’ core behavioural needs.

For a detailed scientific critique of WelFur (and related claims), see:

For a focused briefing on why cage enrichment and “alternative cage designs” do not resolve the major welfare harms, see:

Is the fur industry growing or declining?

Fur farming is widely described as a sector in long-term decline, especially in Europe.

A major 2025 economic analysis finds that EU fur farming has dramatically declined over the past decade, with large falls in the number of farms, the number of pelts produced, and the value of sales. It also concludes that the sector has been unprofitable for several years, and that once environmental and public health costs are considered, the industry’s total contribution becomes even more negative. See:

Action Is Still Needed

While the decline of fur farming is promising, the fight for animal welfare is far from over. Politicians need to take decisive steps to enact full fur production bans and sales bans, to bring an end to the inherent cruelty in the fur industry. Consumers can contribute by choosing cruelty-free alternatives and supporting legislative efforts to end fur farming globally.

The evidence is clear: fur farms are an outdated and inhumane industry that prioritises profit over animal welfare. As awareness grows, so does the urgency to dismantle this cruel practice and move toward a more ethical future for both animals and the planet.

Sources

Key evidence used and recommended for further reading:

EFSA (2025) Welfare of mink, foxes, raccoon dog and chinchilla kept for fur production

Pickett & Harris (2023) The Case Against Fur Factory Farming in Europe

WHO/FAO/WOAH (2021) SARS-CoV-2 in animals used for fur farming (GLEWS+)

Explore the data

For charts and country-by-country visuals on fur production and trends, visit:

Farmed fur production in 2023, by country

Mink fur production 2010 - 2023 (x1000)

Fox fur production 2010 - 2023 (x1000)